|

The dream kicked off in March with our research and distilling class in Seattle. Since then our lives have been propelled forward with our passion! After receiving our approval from the TTB and having our Federal license in hand, we began clean up and construction of what was to be our weekend home for the remainder of the year! We began construction the last week in September, transforming an old workshop into a small 'mom and pop' craft distillery. Only able to drive the 2 1/2 hrs to work on available weekends, we've managed to accomplish a tremendous amount over the last three months working only 17 days with a total of 192 team hours! BEFORE | 9.26.2015 PROGRESS UPDATE VIDEO BLOG | 12.20.2015 The holiday movie season is here! This year brings us the next installment of the Star Wars legend, among other promising films.

Thinking of Star Wars often brings to mind the iconic Cantina scene. Just what were those aliens drinking? Bantha Blaster? Pink Nebula? Romulan Ale? Maybe, but that reminds me that there are many identifiable (and very real) adult beverages that have been featured in Hollywood films throughout the years. Here is a list of blockbuster booze and legendary film cocktails that I put together:

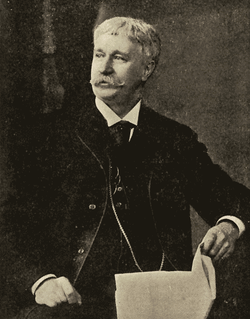

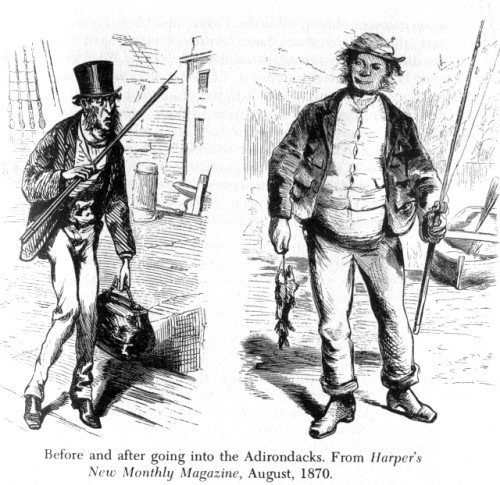

Perhaps you can think of some others?  Adventures In The Wilderness by W.H.H. 'Adirondack' Murray Adventures In The Wilderness by W.H.H. 'Adirondack' Murray In the summer of 1869, the Adirondack Mountains were overrun. Thousands of middle-class urbanites from Boston, New York City and other civilized regions along the east coast left the comfort of their homes and rushed into the unknown wilderness. The hordes of city dwellers included men, women and even entire families. They went seeking a storied wilderness of great restorative and even curative powers. These would be adventurers were informed by one man, a preacher from Boston. They heeded his words and followed. The words of this burly Boston preacher, William Henry Harrison Murray, were set forth in a newly published volume entitled Adventures in the Wilderness, or Camp Life in the Adirondacks. The book had only been released in April of 1869, but was already in its tenth printing by the end of that summer. Educational, eye-opening and funny, thousands of copies of the book were sold to a public hungry for the promises of an accessible, but unexplored great wilderness. The reading public that got its hands on Adventures were not, by and large, satisfied with simply reading about the Adirondacks. Instead, many decided to accept the author’s invitation to adventure into the restorative wilderness themselves. Those readers took advantage (or so they thought) of the author’s detailed instructions on trip preparation, as well as how and where to go once civilization was left behind. A special tourist’s edition of Adventures even included a map of the region and train schedules from several of the metropolitan departure points. The 1869 pilgrimage into to Adirondacks became known as The Murray Rush shortly after that first summer, and retains that moniker some one hundred forty years later. In reality, The Murray Rush lasted nearly five summers, from 1869 through 1874. It was that first June in 1869, though, that marked a seminal moment in the social history of the United States, and led many to refer to W.H.H. Murray as the father of the outdoor movement and camping in the United States.  Growing number of craft distillers creates more opportunities for NY farmers. Growing number of craft distillers creates more opportunities for NY farmers. Craft beverages are not just wonderful experiences and expressions of local, artisanal efforts, they have an important impact on the economy. In a comprehensive 2013 study of the craft beer industry in New York State, Stonebridge Research Group LLC (click here for study) found that the craft beer industry alone had a $3.5 billion impact on New York’s economy. That impact included over 11,000 jobs generating $554 million in wages, $748 million in state and local tax revenue, and $450 million in tourism expenditures. A similar study (click here for study) conducted in California revealed that craft brewers had a $4.7 billion annual impact in that state. These are momentous figures, and it is expected that craft distilling will follow in craft brewing’s footsteps, generating jobs, tax revenue and tourism on a local, regional and state basis. Like craft brewing and craft wineries, craft distilling in New York State is all about utilizing local resources to create amazing, artisanal products. The growing number of distillers in New York will steadily increase use of New York State grown grains and other produce. That means more money and productivity for our farmers. We know, based on the experience of states like California and Oregon, as well as the craft breweries and wineries, that, as new craft distillers appear on the map, tourism is positively impacted. The experience of craft spirits is not just about going to the liquor store and picking up a local artisan’s product. Imbibers of craft spirits want to see where and how the spirits are made. They want to speak to the artisans and learn about the spirits. This desire to experience drives tourism. The state of craft distilling in New York is healthy and headed to new heights. This is a thrilling time for distillers and consumers of spirits. Each time someone chooses to experience craft spirits, the economy of the State of New York and the locality is boosted a bit more. What a great and fun way to support our neighbors and fellow citizens. Cheers! No More Care Free Weekends and We Couldn't Be Happier!  Murray's Fools Distilling Co. Construction | 09.25.2015 Murray's Fools Distilling Co. Construction | 09.25.2015 I've always heard that when you are doing something you are passionate about it does not feel like work. This has never been truer in my own life then at this time, when Sarah and I are planning and building out our small craft distillery in upstate New York. We research and plan all week, in between our day job and family commitments, then spend the weekends implementing our plans. Quite a bit of manual labor happens during Saturdays and Sundays, but it never seems burdensome. There is something about the building of this business from the ground up that instills in both of us a fulfilling and exhilarating sense of mission and partnership. Current plans are for all the permits to be in place and to have the stills running by January 2016. That is just a few months away, and there is plenty of work that must be done in order to meet that goal. Fortunately, our passion drives us and picks up the slack when any mental or physical fatigue threatens. When we do get frustrated or tired, we still smile. This is our dream. This is ours.  William Henry Harrison Murray William Henry Harrison Murray One hundred and forty six years ago, in the summer of 1869, the Adirondack Mountains were overrun. Thousands of urbanites from Boston, New York City, and other civilized regions along the east coast, left the comfort of their homes and rushed into the unknown wilderness. They went seeking a storied wilderness of great beauty, restorative and even curative powers. These adventures were informed by one man, a preacher from Boston. They heeded his words and followed. The preacher from Boston was William Henry Harrison Murray (“Adirondack Murray”). Murray’s book Adventures in the Wilderness gave rise to the “Murray Rush” and “Murray’s Fools,” the movement and moniker applied to those citizens who ventured into the wilderness and found themselves, at first, unprepared for its obstacles. Despite severe challenges, the brave souls who sought out the restorative Adirondacks that Murray wrote about that first summer of 1869, and who often did not make it into the woods due to logistical log jams, did not give up. From 1870 to 1874, Murray’s Fools poured into the Adirondack region with much success. Murray’s advocacy of restoration and recreation found a willing ear among the growing middle class of late 19th century America. Not only did the vacation begin to be recognized as a necessary part of urban life, wilderness appreciation increasingly became a marker of social class. It was in the spirit of Adirondack Murray and the determination of Murray’s Fools that my wife, Sarah, and I began to dream about starting our craft distillery. Soon after, we found that dreaming was not enough for us. We needed to act. That meant taking classes, reading books, and studying the industry we inspired to join. Those preliminary acts culminated in obtaining our Basic Permit from the Alcohol & Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau – the permit that allows us to distill spirits. With our federal permit in hand, we are embarking on the next phase of putting our dreams into action – setting the distillery up and obtaining our New York State permit. Like the travelers to the wilderness of the early 1870s, we face many unknowns and challenges; but also the promise of something wonderful. "We live within-doors too much to be happy. We should seek more variety. Life becomes too much of a routine, an exhibition of one and the same experience. We should open ourselves up to the exhilaration of incident. We should go forth and stand in the midst of many objects, and rejoice our eyes with varied sights and court contact with the accidental and the romantic." - W.H.H. Murray | From Lake Champlain and Its Shores (speaking about Outdoor Life) |

Randall Beach

Co-founder of Murray's Fools Distilling Co. | Altona. NY Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed